Suppose, as many do, that we want to estimate the effect of an action (or treatment) on an outcome. As an example, we might be interested in estimating the effect of receiving a drug vs not receiving a drug on the incidence of heart disease. In an ideal futuristic world, we would take each individual in our population and split them into two identical humans: one who receives the treatment and the other who doesn’t. Since these two humans are 100% identical in every way other than the treatment received, any difference we subsequently observe in their outcome (i.e. development of heart disease) must be due to the effect of the treatment alone.

Unfortunately, since our humble 21st-century technology does not yet posses a human-duplication machine, the natural thing to do is to split our existing population of humans randomly into two groups: those who are to receive the drug (the treatment group) and those who won’t (the control group).

Since there was nothing special about how we determined who gets the drug and who doesn’t, on average, there should be no difference between the treatment group and control group other than in the treatment itself. Thus, comparing the incidence of heart disease in the treatment group and in the control group should give us a reasonable estimate of the average effect of the treatment in the population.

Unobserved confounding in observational studies

While the randomized experiment is a perfectly reasonable thing to do in many situations, unfortunately there are many more scenarios where we can’t just randomly assign the treatment. For instance in the case of the effect of organ transplants on survival, it is probably not the best idea to randomly assign transplants to people. Instead, those who receive transplants first are those who need it the most. Such a study is necessarily observational: we simply observe who happened to receive a transplant based on the existing system.

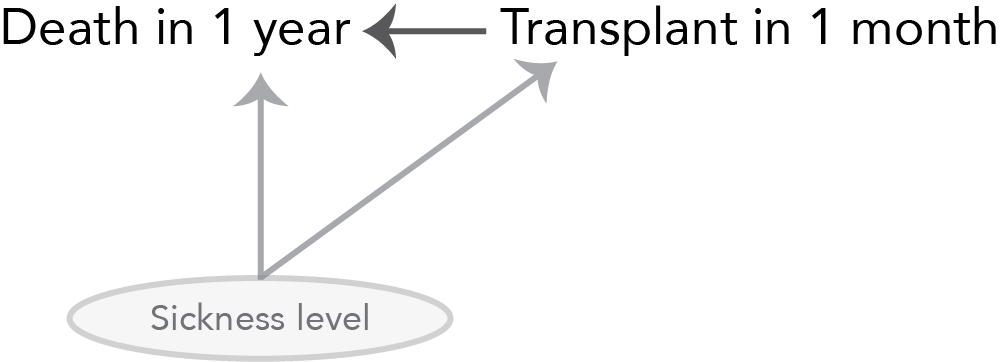

It is highly likely that there will be fairly extreme differences between those who receive a transplant earlier and those who receive one later; namely that those who are transplanted earlier are much sicker than those who are transplanted later. Thus, differences in survival between those who receive a transplant within a month (our definition of the treatment group) and those who receive a transplant in more than one month (our definition of the control group) cannot be attributable solely to the time of the transplant itself, but also to the fact that the earlier transplantees were sicker at the start of the study. Thus sickness is a confounder: something that is different between the treatment and control groups other than the treatment itself that also affects the outcome.

If you’d like to quickly brush up on your causal inference, the fundamental issue associated with making causal inferences, and in particular, the troubles that arise in the presence of confounding, you might like to take a peak at my earlier post on this topic.

If a confounder is observable, you can adapt your estimator using methods such as matching or regression adjustment to obtain an unbiased treatment effect estimate. The key issue that I will explore in this post is what to do when you have unobserved confounding. For example, what if we cannot quantitatively measure “sickness” (the variable that determines whether you will be transplanted soon or not) and so transplants between blood-type compatible donors and recipients are assigned primarily based on sickness as measured by a doctor’s intuition (a fundamentally unmeasurable quantity). Note that this isn’t actually how transplants are allocated, but it will serve nicely for instrumental variables explanation purposes.

What is an instrument and can I play it?

In most situations, if you have an unobservable confounder, there isn’t too much you can do to get around it since changes in the treatment will necessarily also change the confounder (in ways we cannot measure), both of which will in turn change the outcome. In this case, there is no way to measure the effect of the treatment alone (i.e. in isolation from the confounder) on the outcome.

In a few situations, however, you will have an instrument. An instrument, it turns out, is not a tuba, a piano, nor a flute, but rather an instrument is a magical measurable quantity that happens to be correlated with the treatment, and is only related to the outcome via the treatment (the instrument has no influence on the outcome except via the fact that it influences the treatment which inturn influences the outcome). The second part of this definition (that the instrument is only related to the outcome via the treatment) is called the exclusion restriction.

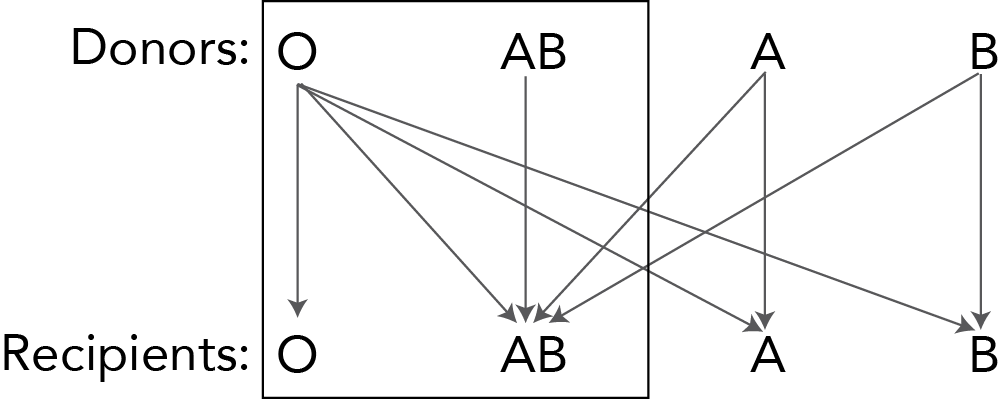

In our transplant setting, a particularly nice instrument is blood type. Patients with blood type AB can receive organs from donors with any blood type (and donors with blood type AB can only donate to recipients with blood type AB), whereas patients with blood type O can only receive organs from donors with blood type O (but donors with blood type O can donate to recipients of any blood type). The result is that patients with blood type O will, in general, need to wait longer for a transplant than patients of a similar sickness level with blood type AB.

Since this is a lot to explain in words, below you will find a picture that demonstrates how recipients with blood type AB have a larger pool of potential donors than do recipients with blood type O. An arrow from a donor blood type to a recipient blood type implies that donors with the specified blood type can donate organs to the corresponding recipient blood type. Since we will focus only on blood types AB and O (pretending that blood types A and B don’t exist for technical convenience), these two blood types have been enclosed in a snug little box within the diagram.

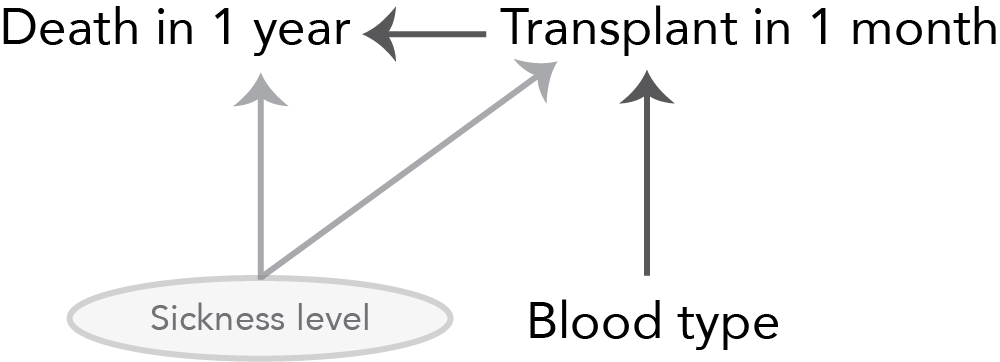

The idea behind instrumental variables is that the changes in treatment that are caused by the instrument are unconfounded (since changes in the instrument will change the treatment but not the outcome or confounders) and can thus be used to estimate the treatment effect (among those individuals who are influenced by the instrument). This idea will be explained in great detail in the next section, but for now I will try to convince you that blood type is indeed an instrument.

Clearly blood type will affect the treatment (whether or not the patient is transplanted within a month), but for blood type to be an instrument, we also need to make sure that blood type has no effect on the outcome (other than through it’s effect on the treatment). That is, we need to check the exclusion restriction. It turns out that, unfortunately, the exclusion restriction is uncheckable (similarly to how it is impossible to check that there are no unobserved confounders). The exclusion restriction will forever remain a critical assumption that will need to be backed up by domain knowledge.

In the blood type case, it is easy to find faults in the exclusion restriction assumption: it is well-known that blood type and race are correlated, and that race and life-expectancy are correlated (implying that blood type and survival might be related via race). However, to keep things simple, we will define our outcome to be a binary variable corresponding to whether or not death occurs within 1 year. It is highly unlikely that blood type will be related to such a short term survival outcome, even via correlation with race. Moreover, blood type is more-or-less randomly assigned (given your parent’s blood type). In this case, the exclusion restriction is fairly plausible, but in many IV setups, a lot of care will need to be taken to back up the exclusion restriction assumption.

Now that we (hopefully) understand what an instrument is, the next question is how to use it (don’t worry if you have no idea why instruments are useful yet, it’s not at all obvious!).

How do instruments work?

Our big question is whether there is an effect of being transplanted within one month (the treatment) on death within 1 year (the outcome). However, our standard approaches to estimating the treatment effect are foiled by the presence of unobserved confounding by sickness, a feature that we cannot accurately quantify. If we could accurately measure an individual’s level of sickness then we could adjust for it using regression adjustment or matching techniques. In our case, however, sickness is defined based on doctor intuition (an unmeasurable quantity), so these traditional approaches to dealing with confounding cannot help us.

Fortunately, we have an instrument (blood type) which modifies the treatment (time to transplantation) without modifying any confounders (the exclusion restriction says that the instrument has no effect on the outcome in any way except through the treatment - this would not be true if the instrument was correlated with a confounder). The exclusion restriction is embodied by the lack of an arrow between the instrument (blood type) and the outcome (death within 1 year) in the graph below.

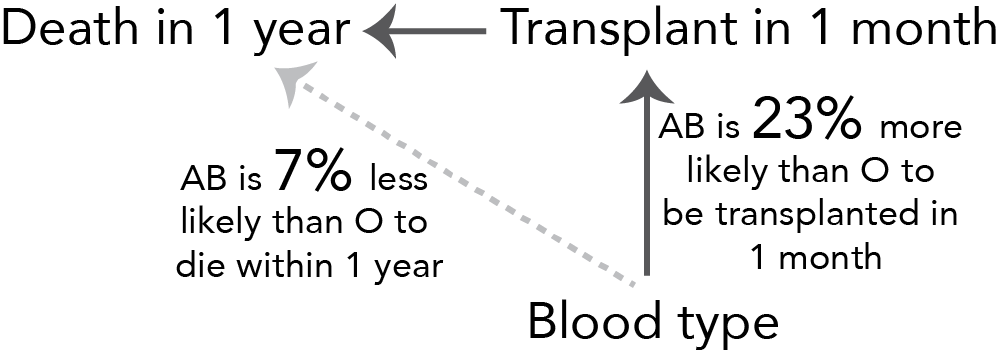

Now, since the instrument affects the outcome solely through the treatment, any observed difference between the outcome (survival) between different levels of the instrument (blood types) must be due to the subsequent differences in the treatment (wait time).

It turns out that the effect of having blood type AB versus blood type O is that an individual is 7% less likely to die within 1 year. Since under the exclusion restriction there is no direct effect of blood type on death within 1 year (except via the treatment), this must be due to the difference in transplant wait time (the treatment) between the blood types.

Since patients with blood type AB are 23% more likely to be transplanted within 1 month than patients with blood type O, we can conclude that the effect of a 23% increase in the chance of being transplanted within 1 month is a 7% decrease in the chance of death within one year.

Mathematically, to scale up the effect of “being 23% more likely to be transplanted within a month” to the effect of “being 100% more likely to be transplanted within a month” (i.e. of being transplanted within a month vs not being transplanted within a month) is equal to

That is, being transplanted within 1 month decreases the chance of death within 1 year by 30%!

It is important to note that since we are estimating the effect of changes in the treatment that were caused by the instrument only (rather than the effects of arbitrary changes in the treatment), the instrumental variables treatment effect estimate is not for the entire population, but only for those who are influenced in some way by the instrument (the “compliers”). Thus this estimate is called the Local Average Treatment Effect (LATE).

The estimator above is often referred to as the Wald estimator and can be written as

In practice, IV is often implemented in a two-stage lease squares (2SLS) procedure that can be shown quite easily to be equivalent to the Wald estimator in simple cases (i.e. when not adjusting for other variables).

Resources

The resource that I found to be most useful was Chapter 10.5 of Andrew Gelman and Jennifer Hill’s book Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models

The series of YouTube videos by Ben Lambert were also really helpful https://youtu.be/NLgB2WGGKUw

Notes

It turns out that you can quantify sickness in the context of liver transplantation using something called the MELD score (model for end-stage liver disease score). But even if we know current MELD score, future MELD score will still be a confounder since if your MELD rapidly increases then you are getting sicker faster and will be transplanted sooner.

If there is anything that is unclear in this post, please feel free to ask questions in the comments section so that I can improve it.